Alamillo Bridge, Spain

|

|

| Alamillo has a very sculptural form, and this design simplicity gives it order. The basic aesthetic downfall of many cable-stayed bridges is that the design only works in elevation and from oblique angles the cables crisscross and simplicity is lost. |

Striking Bridge with Elegance

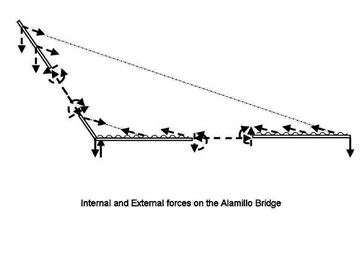

The Alamillo Bridge is a clear example of an unconventional long-span cable-styled bridge; its structural configuration has never been attempted before. It is a cable-styled bridge that crosses the San Jeronimo meander of the Guadalquivir River and is bounded by the ring road of Sevilla in the west. The originality of the design lies in the fact the load borne by the cables supporting the deck over the river is compensated not by traditional back stays but by the considerable backward inclination of a massive reinforced concrete tower, so that the resultant of its self-weight, composed of the resultant of the stay forces, follows the direction of the tower.

The Alamillo Bridge was built more as a monument rather than a piece of structural art. While the leaning mast is very suggestive that the bridge is solely supported by the cables, there is controversy that the deck is mostly self-supporting, since the tension in the cables seems lower than would be expected. To be a good example of structural art, the bridge must also be successful at structural engineering design.

|

Santiago Calatrava Valls, a Spanish neofuturistic architect, structural engineer, sculptor and painter designed Alamillo Bridge. He established his name as a bridge engineer with the Felipe II Bridge, built for the 1992 Barcelona Olympics. In 1987, he won the commission for a new bridge to join Cartuja Island in Seville, the site of the 1992 World Exposition (Expo ‘92), to the mainland across the Guadalquivir River. Alamillo is one of six bridges built for the Exposition, but is by far the most memorable. The bridge crosses a man-made channel that forms part of Seville’s flood relief system. With equally good founding conditions on both banks, the obvious choice for the bridge would have been an arch, putting equal loading on either side of the channel.

This was not to be, although Calatrava’s original concept was symmetrical on a much larger scale, comprising two cantilever spar, cable stayed bridges, with their inclined pylons forming an imaginary gateway over the site. In the event, for both economic and political reasons, only one was built, and has remained an icon of bridge design and engineering ever since.Calatrava’s final design is complex and substitutes traditional stay cables with the weight of an inclined concrete and steel pylon, something that had not been attempted before.

The pylon itself rises 141m above the city, with an inclination of 320 to the vertical, and the deck has a clear span of 186m. From the counterbalancing pylon, pairs of cables support a central spine beam of prefabricated hexagonal shaped steel box sections running the full length of the bridge, from which the road deck itself cantilevers transversely. The bridge has provision for both pedestrian and vehicular traffic.

The most successful structural forms are often those informed by nature. Calatrava’s functionalism is often derived from nature; he famously keeps his dog’s skeleton in his office. Whilst this was not a specific influence here, the link to nature is clear; the deck beam acts as the bridge’s spine, supporting the roadway on ribs of steel. The inclined pylon also emphasises the male form, while Calatrava himself cites a flying bird as his main inspiration.

Aesthetics

Alamillo is a beautifully proportioned bridge. The deck itself flows smoothly over the water, drawing the eye along and up the inclined spar. There is an excellent balance between light and dark, and the deck itself appears as a particularly slender element. This is achieved by the steep angle of the cantilever beams that cast the under deck into shadow. The pylon is much heavier than the deck, and thus gives us the impression that it is the principal member in the load system, but still has many design subtleties to reduce its impact. The hexagonal cross section puts three sides in shade and a channel running the length of the pylon catches the light, reinforcing the impression that it is half its actual depth.

Alamillo has a very sculptural form, and this design simplicity gives it order. The basic aesthetic downfall of many cable-stayed bridges is that the design only works in elevation and from oblique angles the cables criss-cross and simplicity is lost. There are two ways of avoiding this – using a single plane of cables, or arranging the cables in harp form. Calatrava makes use of both of these devices here. Pairs of cables are taken down from the pylon in a harp arrangement, meeting the deck either side of the pedestrian walkway. This harp arrangement is a less efficient way of supporting the deck, but is more aesthetically pleasing.

|

|

| The bridge’s pure white colour accentuates it against the typically clear Spanish sky, with the cables and spar standing out particularly well. |

As this is a pedestrian bridge, design refinements are important as they will be experienced at close hand. For example, the lighting on the bridge is provided by low-level luminaries, rather than lampposts, which would vie with the pylon for dominance of the vertical plane. The pedestrian pathway has a disappointing tarmac finish, but the guard rails that run along the bridge have an interesting texture and design. Mimicking the pylon, these guard rails slope backwards away from the deck, and are topped with concrete along which runs a smooth stainless steel handrail. The smooth surface of the spar is painted matt white, giving a crisp appearance. The bridge’s pure white colour accentuates it against the typically clear Spanish sky, with the cables and spar standing out particularly well. The simplicity of the colour scheme complements the bridge design, leaving its striking form unspoilt.

|

The daring design, its simplicity and its surprising methods of construction all give it the edge over more conventional bridges. The smooth surface of the spar is painted matt white, giving a crisp appearance. The bridge’s pure white colour accentuates it against the typically clear Spanish sky, with the cables and spar standing out particularly well. |

Structural Design

The inclined pylon of Alamillo had no structural precedent. The conventional cable stayed design would consist of two decks of similar span to minimize possible bending moments in the pylon. Unequal spans require decks of equal weight, but this is hard to achieve, and so back span cables are anchored to the ground to take the variation in forces under pattern loading conditions.

The deck of the bridge, with a 200m span, is supported every 12m by a pair of stays. A total of 13 pairs of cables are used. In the transverse section, the deck is composed of a large steel girder with a hexagonal box section 4.4m high and 5.6m wide, from which 12m long transverse steel ribs arise every 4m, supporting a 230mm thick concrete slab. The stability of the bridge depends on an exact balance between the moments originated at the base of the pylon by the weights of the deck and pylon. During the construction process, it is not possible to avoid the errors in geometry and weight inherent in any real construction project. Because of the unconventional structural design and the short period of time available for construction, the building sequence was also quite different from the standard construction methods used in cable-stayed bridges, where, normally, the first step is the construction of the tower. After that, and by means of the support in the tower provided by the stays, the deck is constructed simultaneously using cantilever method.

|

In the Alamino Bridge, the construction sequence was completely different. The steps of construction are as follows:

- Construction of the foundation and temporary backfill of the river

- Construction of temporary piers to support the deck elements

- Construction of the deck over the temporary piers

- Construction of the lower part of the pylon

- The rest of the pylon was built in segments and stabilised by the deck and the progressive placement of the stays.

It was ensured that:

|

- Erection of the steel segment of the pylon and welding to the previous segment

- Placement and tensioning of a couple of cables

- Placement of reinforcing steel and concrete filling of segment

|

The design and construction of the Alamillo Bridge provides an insight into one the best Architectural and Engineering minds of our time. The cable stayed cantilever spar concept has been since been replicated, both by Calatrava and others, and is now an established, if expensive, form of bridge construction. Calatrava provided a fresh take on the idea with the Puente de la Mujer in Buenos Aires, a bridge that opens to river traffic. The faith that the Council of Seville put in both the design and construction teams has truly paid off, and this innovative bridge is a complete success.

References:

http://www.bristol.ac.uk/civilengineering/bridges/Pages/NotableBridges/Alamillo.html

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02321263#page-2

http://people.bath.ac.uk/jjo20/Site/Publications_files/ORR%20PAPER%2001.pdf